The Making Of the California Gharana

Noelle Barton

Please begin by telling us a little about yourself and your dance journey. When did you begin studying kathak, what were your initial impressions of the dance form, and what most attracted you to the dance?

Please begin by telling us a little about yourself and your dance journey. When did you begin studying kathak, what were your initial impressions of the dance form, and what most attracted you to the dance?

I’m a firm believer that nothing happens by chance. It’s as if I was predestined to be a kathaka. My childhood wasn’t the usual one. My parents were entertainers and I was raised on the road, a backstage baby playing in the wings during rehearsals. Theater life was a familiar environment. My mother sang and danced. My father acted, sang, wrote plays and was a female impersonator. My favorite play was The King and I, a musical. My dad played the king; a flamboyant, charismatic, dramatic presence. I was enamored by the elaborate Asian costumes, sets, and customs. I was three, but I already knew I was a dancer.

I studied ballet and classical piano for 4 years. But, when I was 13, I rebelled when my father died suddenly. Dropping classes, I left home at 15 and immersed myself in the sixties counterculture movement. I went barefoot and wore 12 brass bells around each ankle which I never removed. Yes, I was a hippie.

I first saw Pandit Chitresh Das (who in my earlier student days we called Dadaji) perform at the San Rafael Improvement Club on November 9th, 1977 with Zakir Hussain and George Ruckert. It was his 33rd birthday. I was amazed by his dynamic energy and drawn to the vibrant rhythms. He slapped his feet effortlessly and seemed to be challenging the drummer to go faster. My dentist had invited me to the concert. I was 26. The day after seeing him perform for the second time, I would be leaving for Nepal with my 7 year old son. I had no plans, but fate obviously did. I returned to live with my mom five months later, broke and sick. My first day out, I saw a poster that Kathak classes were being taught by Chitresh Das at the Belrose Studio in San Rafael. I decided to check it out. I already regarded myself as an established dancer in my own right. I copied the free form expressive moves of Isadora Duncan and Martha Graham. I’d danced onstage with the Grateful Dead for over a decade and performed in plays and improv groups. I thought I’d just drop in and take a few lessons so I could incorporate these interesting movements into my own dance form. Yes, I was consumed by my own greatness. My ego more than outweighed my talent. Dadaji had never seen such audacity. He used to say, “Noelle, she has a swollen head.”

My first class was on April 16th, 1978. I showed up early. Gretchendi [Gretchen Hayden] was setting up a rug, flowers, incense. Others arrived and greeted her. Dadaji had just returned from a tour of India with his first group of American dancers. I was unaware this was his first class since separating from the Ali Akbar College. There was only one level back then and new students danced in the back and floundered until an advanced student helped you figure out the footwork or composition. Gretchendi set the finest example of an elder guru-sister. I’d watch her feet. A few months later, classes moved to the Knights of Columbus building in San Anselmo, which would become our main hub for over a decade.

I loved the dance, the vigorous footwork, the dizzying turns, the recitation. It’s the mathematical element that has always attracted me most about Kathak. I loved the complex rhythms and the dance, but I never intended to stay or become a kathaka. I had a huge ego and a stubborn will. Dadaji knew I would be a challenge to tame. So one day as we were sweating through our hundredth grueling cycle of tatkar, he stood within inches of me and stared into my eyes, unimpressed, and said, “In the dance many will come, and many will go… the weak ones always run away!” Well, the challenge was on. How could I leave now?

What was the sociocultural environment like in the early days of your learning? What was the energy like in Pandit Das’ classroom and/or on the stage when he performed?

What was the sociocultural environment like in the early days of your learning? What was the energy like in Pandit Das’ classroom and/or on the stage when he performed?

Classes were soooo different then. First of all there weren’t as many students, so we got a lot of one-on-one attention. He made us recite loudly every syllable as we danced, building intense stamina and endurance. After three hours of dancing we would sing, recite and write down compositions. He expected us to have bells on and be sweating when he arrived. Often, if you weren’t dancing up to par, you were told to sit down, watch and recite. That seemed like punishment at the time, because all we really wanted to do was dance.

About a dozen students started class in the summer/fall of 1978. Michele Zonka, Joanna Dunbar [de Souza], and Amrit Mann (my lifelong guru-sisters) started on the same week at the Cultural Integration Fellowship in San Francisco, where he held classes every Saturday. Dadaji had nicknames for his students. Michele, Joanna and I were his “Wolves.” He didn’t drive a car back then. So for many years Joanna, Michele and I picked him up at 9 a.m., making a loop around the Bay teaching classes, returning to Marin at 6 p.m. Between classes, as we drove, Dadaji would recite new compositions that we wrote in our journals. Every car ride with him was an intensive, especially on long eight-hour drives to teach in Los Angeles.

We all lived within a mile of dance class. For a few years Joanna, Michele and I shared the same house. We went everywhere together. We recited as we walked to class. After classes we’d go over the new material. Reciting and dancing was never-ending in our household. Classes were five or six days a week and rehearsals were a few evenings a week. After class, which ended after 9pm, we’d walk with Dadaji to the pizza place for dinner. He was always reciting and brainstorming. During one of those late-night-walks, I explained to him that the American audience didn’t get the mathematical element of Indian music and dance. They needed to be educated. That’s when the phrases “organic math” and “meditation in motion” were first coined. Years later Michele coined the phrase Kathak Yoga.

Not being in the professional work world, many of us didn’t earn a lot of money. Whatever we earned we put toward our tuition. All our money went into the dance. Even with the grant money, we had to do much of the work. We designed our posters, (laid out by hand, before computer graphics!), we did the mailing lists late at night, and sold tickets (by word of mouth). We sewed our own costumes from the cheapest kitchen curtain material and glued on sequins. We designed and made props with paint, glue, duct tape and cardboard. The day before a concert we’d make hundreds of samosas for intermission. Then on the day of the show, we were roadies: we unloaded rugs and stage props and set up the concert hall. Then with our costumes and bells on, we’d wear headsets to give lighting and sound cues from the wings before running out on stage to perform. The company couldn’t afford to hire people to do all that work. We performed to sold-out audiences—mostly friends, musicians, and students—and then we’d pack it all up again and go home. A very close bond developed between the three of us. Dadaji would say about his Wolves, “I feed them knowledge and they chew my hand off.” But he knew the level of our devotion. We dove into the dance and immersed ourselves in his teachings. We couldn’t get enough of the dance.

Not being in the professional work world, many of us didn’t earn a lot of money. Whatever we earned we put toward our tuition. All our money went into the dance. Even with the grant money, we had to do much of the work. We designed our posters, (laid out by hand, before computer graphics!), we did the mailing lists late at night, and sold tickets (by word of mouth). We sewed our own costumes from the cheapest kitchen curtain material and glued on sequins. We designed and made props with paint, glue, duct tape and cardboard. The day before a concert we’d make hundreds of samosas for intermission. Then on the day of the show, we were roadies: we unloaded rugs and stage props and set up the concert hall. Then with our costumes and bells on, we’d wear headsets to give lighting and sound cues from the wings before running out on stage to perform. The company couldn’t afford to hire people to do all that work. We performed to sold-out audiences—mostly friends, musicians, and students—and then we’d pack it all up again and go home. A very close bond developed between the three of us. Dadaji would say about his Wolves, “I feed them knowledge and they chew my hand off.” But he knew the level of our devotion. We dove into the dance and immersed ourselves in his teachings. We couldn’t get enough of the dance.

The Indian music scene was flourishing in the Bay Area in the late 60s and the 70s. Our audiences were enthusiastic and came to every concert. We had a devoted audience, mostly because of the hippie scene with its often naive interpretations of India’s spiritual ideology and mysticism. The Beatles and Sandy Bull had already introduced Ravi Shankar to some Westerners.

In 1967, Don McCoy, a family member of mine, contributed $20,000 to Khansahib [Ali Akbar Khan] to establish his dream of a school of Indian music and dance in America. Those were the seeds of dreams.

George Ruckert was there during those very early days of the College. He recently reminded me that Khansahib, Zakir Hussain, and Dadaji were on a quest to perform wherever and whenever possible. There were concerts every weekend in churches and theaters in San Francisco and Berkeley. As new students we did our first performances at schools, in nursing homes, at county fairs, and home concerts.

What kinds of challenges did Pandit Das face in his earlier years of teaching and performing in the US? And in your experience, what challenges and opportunities did the Chitresh Das Dance Company face, both in the US and in India?

What kinds of challenges did Pandit Das face in his earlier years of teaching and performing in the US? And in your experience, what challenges and opportunities did the Chitresh Das Dance Company face, both in the US and in India?

One thing about Dadaji, he was able to adapt with the times. He realized that the American audience wouldn’t sit through a three-hour concert, no matter who was performing. He created pieces that were ahead of their time: Energy, Class Tech, and Rhythmics, which eventually led to Gold-Rush.

In America, we were dubbed “The Pioneers of Kathak Dance” by SF dance critic Alan Ulrich in 1980. During that same year, San Francisco’s Ethnic Dance Festival was only a few years old. My belly dancing friends had performed the year before and I kept thinking, “Why aren’t we in the festival?” But whenever I mentioned it to Dadaji he rejected the idea because of the term “ethnic.” He was offended and said, “Kathak is a classical art, not an ethnic dance.” I kept trying to explain to him: Americans refer to anything that originates from another culture as ethnic. He didn’t want to hear any of it. It was Christmas of 1980. He was away on tour in India. Gretchen, Michele, Joanna and I decided to call him and beg him to allow us to at least audition for the Ethnic Dance Festival. Reluctantly, he gave us permission and we landed the audition. We performed in at least twenty annual Ethnic Dance Festivals over the past four decades. We also performed in the 1984 Olympics, and for the World Drum Festival at Washington DC’s Kennedy Center in 1987. Another highlight was performing on the same bill with Ravi Shankar in Berkeley.

In India, it was a risky challenge for him to present his American students. At first we were viewed as a novelty. But eventually we proved our merit. At the end of the 1981–82 tour, Dadaji and the Company, which had dwindled down to Julia [Maxwell], Marni [Wieser Ris], Batina and myself, performed on national television. Back then there were only three channels showing old 1950s American TV programs. Imagine my surprise when twenty years later on a visit to Darjeeling I saw our performance on TV.

We toured by train across northern India. Sometimes to great acclaim and other times to skeptical reviews. Unlike his tours in later years, in those early days no one met us and took us to a hotel. On our tour in 1981–82 we arrived in Kolkata: 15 dancers including Dadaji’s wife Julia, sarodist Christopher Ris, my 11 year old son, and Dadaji. We were then informed our living arrangements had fallen through and we had no place to stay. Back then you had to bring everything with you, contact lenses and solution, batteries, iodine crystals to purify water, hair dryers, real chocolate! We each lugged heavy footlockers.

The first night we camped out in Dadaji’s childhood friend’s house, sleeping in the living room, under dining tables with mosquito nets, and on the veranda, until all the dancers got rooms at the YWCA for $5 a night which included breakfast: a hard-boiled egg, toast and chai. The YWCA was halfway between Flury’s Bakery and Mother Teresa’s Mission, and just a short walk to New Market. The week before Christmas nine of us, Dadaji included, shared a two-room flat on Merlin Park Road. It was a few miles walk from Birla Academy where we rehearsed and had class. During load shedding [periods when the power would be out for areas of a city], we carried buckets of water up flights of stairs to bathe. We washed our clothes on the roof, shooing away giant crows. It was definitely an adventure like none other. ITC sponsored the tour. Sometimes after a concert, late at night, we had to walk around carrying our heavy costumes and bells, searching for a cab driver who would take us back to Ballygunge.

That tour was fraught with ups and downs. Lack of funds, lack of accommodations, etc. The concerts were always well received by the audiences. But, because of tradition and rivalry between gharanas [lineages of dance and music] some critics would write less-than-complimentary reviews. Dadaji had new ideas which challenged “tradition” and they questioned whether it should be acknowledged. That tour was far from easy. By the end of three months only six of us returned from that tour together; Amrit, Batina, my son and I, and Dadaji and Julia.

I only wish I’d been a more knowledgeable student at the time. We performed in the homes of very prestigious musicians and dancers and we were clueless to the incredible company we were in. The dynamics of some of the events I witnessed while performing and traveling with Dadaji were out of my league to understand or appreciate fully. One night we were treated to an evening at the home of Vilayat Khan, where we shared dinner with his mother, two sons and his daughter, and then were treated to a private concert by him and his adult children. It was a mind-blowing experience.

While on that India tour, a group of us decided to visit Kathak Kendra to watch a class taught by Pandit Birju Maharaj. After his class ended, he asked us how his teachings differed from Dadaji’s. We were put on the spot. I wasn’t impressed with the reserved image the few advanced students were giving, so my big ego decided to offer up a vibrant example. I was only a three-year student, and before I realized what I’d done, I started reciting a complex chakradhar tihai. The recitation went well, but then I had to dance it, while Pandit Birju Maharaj and his entire class and musicians kept tal. I prayed as I took those 35 turns that I’d end on sam. Talk about being put under a microscope! I never told Dadaji about that experience until decades later.

I recall a concert in Patna that stands out from the many concerts we performed. It was near the end of our tour. There was a huge billboard announcing there would be ten American dancers, but by then it was only Marni, Batina, myself, and Julia left. The stage was plywood covered in burlap which bounced if we danced too hard. The crowd was loud and rowdy. Shortly after Dada came onstage, the power went out because of load shedding. He had just begun his 81 turns. Police came to protect us in the wings and they shined flashlights on his feet. From my sightline I could view him turning. As he looked out into total darkness with nothing to spot on, he turned without drifting an inch and ended on sam to a roaring audience. He had won their hearts. I also treasure the last few weeks of that tour when my son and I lived at the home of Ma and Baba, Dadaji’s parents. His mother loved my son and she would tease him, saying she was going to adopt him and raise him as her own.

Dadaji’s way of teaching evolved in the mid-eighties when a large Indian population migrated to the Bay Area. He began children’s classes in San Pablo and Berkeley where nine-year-olds Antara Bhardwaj and Labonee Mohanta began their studies. In 1988, he got the opportunity to teach at San Francisco State University and he had to create a curriculum for the classes. Michele and Gretchen helped design a course that could be credentialed. But really, what can a student know about kathak after a college course?

Like I said before, I don’t believe in coincidences. In December of 1997 while visiting Kolkata I met up with Ritesh (Dadaji’s brother) and Joanna who were there on tour with the Toronto Tabla Ensemble. It was the day before Christmas. I had plans to leave the next day for Darjeeling. They insisted I go with them to the airport to get Dadaji. I hadn’t seen him in a few years and I was the last person he expected to see in India. Later, as we ate dinner, he gave me the third degree. “Where have you been? How’s your son and your mother? Why aren’t you dancing?” I had never stopped dancing. I had taught some classes to Girl Scouts and performed in small venues, but I didn’t tell him that. He’d just say I had a swollen head.

When I returned in 1998, the classes had been altered again. The footwork exercises were different. Pranam was shorter. Jatis and bhants weren’t emphasized as much. Classes weren’t as long, so much fewer cycles were dedicated to each exercise. Singing of devotional songs was more prominent. I was never great at singing, I have a low register and it’s difficult for me to hit the high notes. It was interesting to come back like a new student, taught by people I didn’t know who’d only been studying for a few years. I knew all the compositions, but a lot of the choreography had changed. I had to humble myself: out of practice, overweight, nine years older, once again I was a new student dancing in the back of the room.

I believe he made changes to accommodate his new audience. The majority of his students were Indian now and he wanted to get everyone dancing onstage. School shows had 300 students of all ages performing with all the mothers helping to maintain order backstage. Though it was nothing like our experience, I was totally impressed by how his classes had grown.

Back in 1980, when we were just sixteen struggling students in class, he would say to us, “I want 500 students and schools around the world. I want to dance with Gregory Hines. I want to leave a legacy of dancers after I’m gone.” And we wondered how he’d ever find 500 students.

He had set goals for himself, to leave a legacy. He lived every breath consumed by his passion, the dance. He also expected, though somewhat unrealistically, that same dedication from his students. We had jobs and children and other family obligations, but to him, those were just excuses.

Kathak Yoga is an innovative practice Developed by Pandit Chitresh Das. What does Kathak Yoga mean to you? Can you shed some light on where and when it was developed?

Kathak Yoga is an innovative practice Developed by Pandit Chitresh Das. What does Kathak Yoga mean to you? Can you shed some light on where and when it was developed?

Kathak Yoga was developed during my absence. I’d studied almost twelve years and finally performed my first solo in the 1989 Asian Dance Festival, the grand opening of the Cowell Theater. My mom was ill, my teenage son needed parenting, and I had moved an hour away from classes. I tried to explain I needed some time to devote to my home life. Then I took an eight-year sabbatical. I didn’t try Kathak Yoga until I returned. I was intrigued, as well as overwhelmed, by the concentration it took to split the mind like that.

“Kathak Yoga” was first performed by Joanna Dunbar [de Souza] and Michele Zonka for a packed audience at Dadaji’s Alma Mater, Rabindra Bharati, In Kolkata in December 1995. Joanna danced and recited bols in Jhaptal and Micheledi danced and recited in tintal. Dadaji had developed it during his eight year break from performing in India, but had yet to perform it himself.

What strikes you the most about Pandit Das’s teaching?

One of the many intriguing qualities that our Guruji possesses is the ability to SEE into each person he teaches. He sees their strong points as well as the blocks that may hinder them from reaching their full potential. Like a diamond cutter, he finds the hidden qualities and polishes them. When I think of the many lessons I learned while under Guruji’s tutelage it was more than lessons about dancing or singing or knowing a lot of compositions. It was more about a way of life. A mindfulness. He’d tell stories of visiting his Guru’s home as a boy and how he was taught to eat without leaving a mess around his plate. How to place your shoes outside the door. Be on time. Show respect to one’s elders. Knowing Dadaji made me accountable.

From my journal entry 12/13/78: “Friday was our last class. It’s Christmas break and Dadaji is going to India. At the end of class he began thanking us for all he learned this year about teaching American women and how he was going to practice everything he learned. Interesting instead of telling us we ‘should’ practice, he shows by example how to be, learn, think, and feel. A tear came to my eyes. I was afraid, in his absence I would lose my self-discipline.”

Dadaji had many sayings:

“Don’t cheat; you are only cheating yourself.”

“Americans are always seeking, but they won’t practice.”

“Stop escaping. Clear your head. Practice harder.”

That was his answer to everything, “Practice, practice, practice!,” as if with enough practice everything else in life would inevitably sort itself out.

Chitresh Das was only human, with flaws like any one of us. He said, “When I point my finger at you, three fingers point back at me.”

He was also an incredible master of layakari [rhythmic prowess] and tyaag [sacrifice], who taught himself to be a teacher. He became a legendary Guru…and I was honored to walk by his side. On my life journey he was an elder brother, a father, a dear friend, and my beloved Guru forever.

While growing up under his influence I learned many things. Endurance, humility, timing, respect, honor, integrity, patience… not that I’m good at those things all the time. But he gave me the tools.

What advice can you share with aspiring and future kathak students?

To the students of the future: A little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. Practice, practice, practice, and always know you must work hard to attain anything in life. Don’t take the easy path. Going through the fire builds strength of character that will carry you through the rough times. Be confident yet humble. And honor your elders for paving the way.

Namaste, Noelle

Noelle Barton

Noelle Barton was born in Hollywood. Raised on the road as a backstage baby, she called Miami Beach, Los Angeles and San Francisco home until her parents finally settled in Marin County, CA in 1960. Dancer, ceramic artist, archivist, and author, Noelle has performed and lived in Nepal, India, and Europe and presently resides in western Sonoma County.

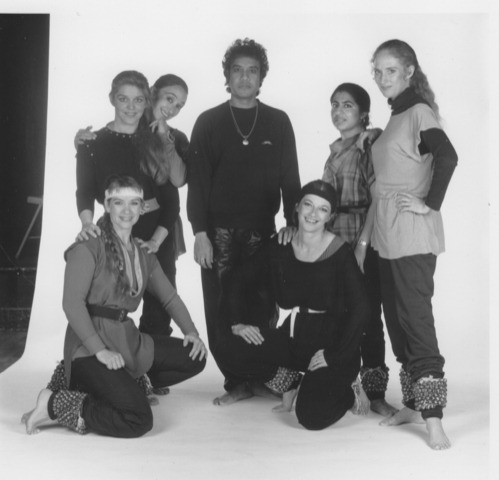

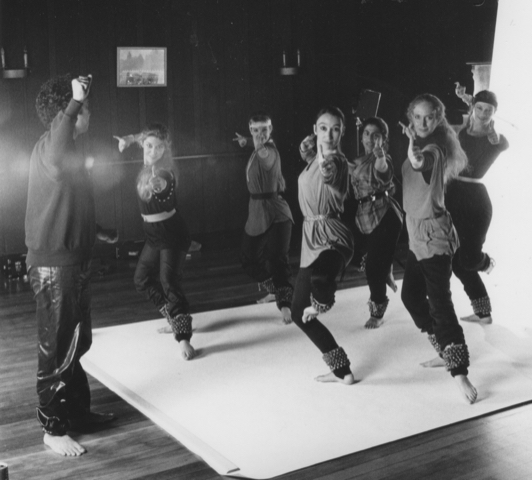

Photo Credits: Photo 1 – photo shoot at Knights of Columbus studio in San Anselmo, photo credit Ritesh Das; Photo 2 – Pandit Chitresh Das and Noelle as Ravan & Sita 1988, photo credit Bonnie Kamin; Photo 3 – Pandit Chitresh Das, Joanna de Souza, Michele Zonka, Noelle Barton, Amrit Mann, Marni Ris, and Julia Maxwell at Knights of Columbus studio, photo credit Ritesh Das; Photo 4 – Michelle Zonka and Noelle performing Daandia Raas at Marin Showcase Theater 1980, photo credit Sandy Barton; Photo 5 – Pandit Chitresh Das and Noelle on her birthday 1978, photo credit Sandy Barton, Photo 6 – 1985, photo credit Bonnie Kamin.

Leela Dance Collective

23650 Community Street

Los Angeles, CA 91304

P: 323.457.4522

E: info@leela.dance