The Making Of the California Gharana

Rukhmani Mehta (previously Rina Mehta)

As a well established kathak dancer, what is it like to look back on your very first experience of kathak dance? What encouraged you to take your first kathak class, and what was your very first class with Guruji like?

As a well established kathak dancer, what is it like to look back on your very first experience of kathak dance? What encouraged you to take your first kathak class, and what was your very first class with Guruji like?

Well to be honest, I never had an inclination or desire to study kathak dance. As a child I had studied Bharatanatyam and when I arrived at UC Berkeley as a young college student, I was looking for a Bharatanatyam teacher to continue my studies. My impression of kathak dance was informed by what I had seen in Bollywood movies – and it looked to me like kathak was about looking pretty and flirting. Bharatanatyam on the other hand seemed to have the rigor and gravitas that I was looking for. I was unable to find a Bharatanatyam teacher and eventually, a friend of a friend invited me to come try a kathak class on Telegraph Avenue. I told her that I wasn’t really interested in kathak and she insisted that I at least come and watch a class.

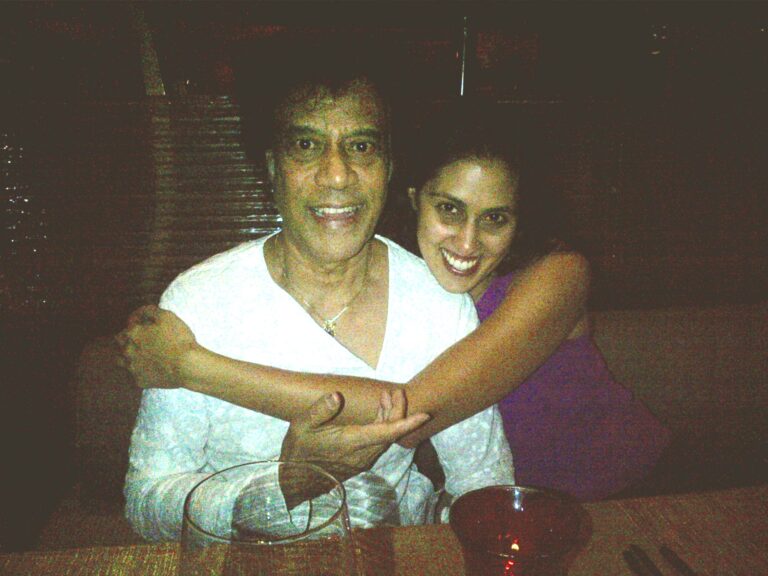

I remember that first visit to Guruji’s class like it was yesterday. Guruji was sitting on the floor playing tabla and singing Holi Tarana. There were nine or ten dancers in the class, drenched in sweat and moving to the music he was creating. I remained mesmerized for the entirety of the class, losing track of time and any other reality aside from the energy of the class. At one point in time a group of Hare Krishnas passed by the front door of the studio. As the sounds of their music and chanting filtered in, Guruji made a pointed joke about how we were invoking the very Krishna that they were searching for. I don’t remember much after that first class. But looking back now, I can see that some part of me made a decision that day to dive into Guruji’s world.

What is it about the art and specifically Pandit Das’s teachings of it that particularly inspired you? Are there any particular aspects that resonate with you the most? Which aspects are the most challenging?

What is it about the art and specifically Pandit Das’s teachings of it that particularly inspired you? Are there any particular aspects that resonate with you the most? Which aspects are the most challenging?

For me, it was Guruji’s approach to the art, what he represented, what he believed that drew me to kathak. He taught me that our journey in life is ultimately spiritual. Whether we choose to be artists, parents, lovers, leaders, servants – it is all spiritual. The pursuit of the art for him was the pursuit of the divine. His willingness to walk his own journey with courage and grace was inspiring to watch. His generosity in guiding all of his students on their own journeys was unbounded.

Guruji taught me that as an artist you are in service to the art, the divine, your students and your audiences. He taught me to be ever humble and willing to take complete responsibility for not only myself but my peers, students, family, community and society. He taught me how to wrestle with and understand ego, open my heart again and again, and be always in service to something greater than myself. Being an artist is to be a spiritual warrior.

And the path of an artist and spiritual warrior is an arduous one. At times it seems that all of it is challenging. Guruji’s mantra was practice, practice, practice. Initially, I understood it to apply to the dance alone. But more and more, I understand that life must be approached like that – practice, practice, practice. Every day there are opportunities to be courageous and open-hearted, to live from a place of grace and love. Guruji’s teachings apply on and off the dance floor and infuse all aspects of life.

You were a member of the Chitresh Das Dance Company from 2004-2015. Can you talk about your experience training and performing with the company, both in terms of your own trajectory in the dance and the trajectory of an Indian classical dance company performing on the western proscenium stage?

You were a member of the Chitresh Das Dance Company from 2004-2015. Can you talk about your experience training and performing with the company, both in terms of your own trajectory in the dance and the trajectory of an Indian classical dance company performing on the western proscenium stage?

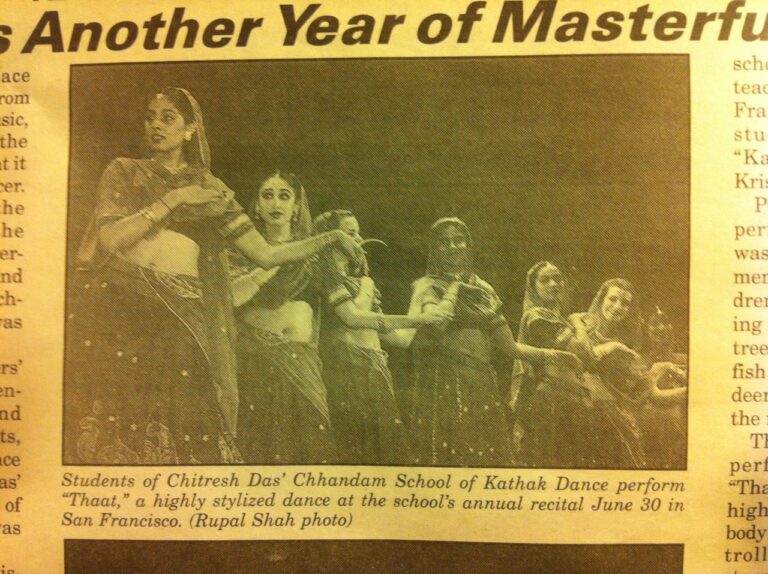

Training and performing with the company was an exacting experience. Guruji, of course, demanded excellence. It was an incredible journey. It is very hard to zoom out and reflect on it because it really was an immersive and all-consuming journey. I feel like once I said yes to being in the company, I was just guided by Guruji, and over the course of dancing and performing in the company, I learned, grew, stretched, and became a dancer. I think being in the company really affirmed for me what is possible in the art form as a company, as opposed to a soloist, what impact company works and productions can have, and how they bring out and communicate very different aspects of the dance which traditional solos do not. I also saw how important productions and choreographic works were to introducing new audiences to the artform and bringing more and more people into the world of kathak dance. Kathak can be inaccessible; it’s ancient, culturally specific, and there is a lot of nuance and sophistication.

For me, watching Guruji create production after production–taking each from concept to music composition to choreograph to performance–it was a great gift that I got to be a part of that process. I really learned what it is to be a choreographer in comparison to an artist. Costuming, lighting, sound, music, dance. All of that is a part of making a production great. I got to see how much Guruji tried to bridge the gap between the artform and the lay audience. Even as he was creating great works of art, ultimately, the intention behind these great works was about connecting to the audience. Also, I think for me, one of the things I thought was fascinating was that Guruji’s works were consistently about uplifting audiences. He wanted people to walk away feeling uplifted. From him I learned that, as an artist, when you are creating you constantly have to think about what it is you want the audience to experience, to have, how you want them to leave, and what you give to them. Watching him over and over give joy and uplift his audiences gave me a sense of his true purpose in the arts.

Lastly, while Guruji really instilled in us the value of the traditional kathak solo–that we have to perform, preserve, and advance that tradition–I feel that creating choreographic works and productions and establishing kathak on the western stage was a big part of his vision, and part of his vision that I always wanted to be a part of. He believed kathak belonged on the world stage side by side along with the best traditions of the world. He wanted to provide kathak dance an elevated place in society, and he believed kathak deserved it.

You faced significant injuries and physical challenges throughout your training as a dancer. Most people would have given up if confronted with the seriousness of the issues you faced. Can you describe what those challenges were and how you overcome them and continue to today?

You faced significant injuries and physical challenges throughout your training as a dancer. Most people would have given up if confronted with the seriousness of the issues you faced. Can you describe what those challenges were and how you overcome them and continue to today?

I was injured within six months of attending my first dance class. One day, quite suddenly, I began to experience intense pain in both of my knees. The pain was debilitating and I saw many doctors, each of whom gave me a different diagnosis. One sports medicine doctor told me that due to structural problems with the placement of my femur bones, I was never going to be able to pursue dance seriously. He prescribed me painkillers and saw me off. I was devastated. I continued to attend Guruji’s class but would sit for the duration of the class–reciting, singing, crying, and watching my peers advance. This went on for eight months as I saw acupuncturists, herbalists, and any kind of alternative health care practitioner I could find. I remember looking to God, trying to understand why I would find a teacher like Guruji and then be confronted with a debilitating injury. Eventually, I found my way to a Pilates instructor who looked at my hips and legs and said that the issue was a simple matter of imbalanced alignment. She viewed the injury as easily fixable and didn’t see any reason why I couldn’t dance. So I began the grueling work of retraining my body’s foundational structural patterns. The process of recovery was bumpy. I would make progress, get excited, overextend myself on the dance floor and reinjure myself. Guruji allowed me to struggle with my body and soul in his class. He gave me modifications, helped me wrestle with my ego, and created an entire low-impact class for me. I was blindly stubborn in my desire to dance, and he was there to provide me with a safe and supportive container within which I could walk the journey I was supposed to. I had incredible support from my guru-sister Seibi Lee, who painstakingly spent hours inspecting my body’s alignment, helping me adjust my technique to avoid injury, teaching me to recite and play manjira so I could stay engaged when I had to sit in class. My injuries were, in some ways, a rite of passage. They tested not only my desire to dance but also my intention. Even now, when faced with an injury, I see it as a sign that I have strayed from the right intention. An injury is a sign that my desire to dance is laced with ego. My injuries help guide me back to a deeper and truer desire to dance–for freedom, joy, and connection.

One of your first roles at Chhandam was in fundraising–one of the most difficult aspects of nonprofit work. Can you speak about how you became so fearless in this daunting work and the importance of fundraising for nonprofit arts organizations such as ours? How did that work lead to your vision to launch the Leela Endowment, which is unprecedented for Indian classical arts?

One of your first roles at Chhandam was in fundraising–one of the most difficult aspects of nonprofit work. Can you speak about how you became so fearless in this daunting work and the importance of fundraising for nonprofit arts organizations such as ours? How did that work lead to your vision to launch the Leela Endowment, which is unprecedented for Indian classical arts?

I had never intended to get involved in fundraising at Chhandam. I came to Guruji to dance. But one day, Guruji walked into class and expressed his intense frustration at the financial difficulties the organization was having as it prepared to present Masters in Performance, a concert featuring Guruji with Pt. Swapan Chaudhuri, at the Cubberley Theater in Palo Alto, CA. My heart sank hearing him talk. I felt indignity and injustice on my Guruji’s behalf. I couldn’t fathom how it was that great artists, tradition – and – legacy bearers such as my Guruji had to struggle for the meager resources it took to organize a small concert. I was compelled to action and organized a campaign to gather ads from South Asian businesses in Berkeley and the South Bay. Together with my guru sisters, we raised $8,000 to help support that concert. Over the next decade and a half, I became increasingly involved in fundraising for the organization’s work. I helped write grants and organized fundraising events. As I advanced in my studies under Guruji, taught at Chhandam, and performed with CDDC, I began to understand how crucial financial support was for the advancement of the art form.

I became increasingly impassioned about freeing artists from the grueling pressure of making ends meet so that they could carry the art form forward. In 2012, I began to talk with Guruji and the team at Chhandam about an endowment. While everyone could see the merit in establishing an endowment, it seemed like a fantasy. How could a small arts nonprofit raise millions of dollars? Three years later, the year of Guruji’s passing, I decided that it was imperative to establish the endowment. Guruji’s sudden passing forced me to face many realities. One of them was the harsh reality that time does not wait for anyone. I began to raise funds for the endowment in earnest. I am very grateful for those individuals who lent me their belief as I started work on the endowment–my mom and my dear friend Trina Chaudhuri. I am grateful for my guru sisters Rachna Nivas and Seibi Lee, who lent the idea their enthusiasm and belief. I am grateful to Dr. Ushakant Thakkar, who was the endowment’s first major donor. His support and encouragement propelled the work forward. I am grateful to the Leela Board of Directors as well as all of the community of donors that have come together to establish the first self-standing endowment for Indian classical dance and music.

I became increasingly impassioned about freeing artists from the grueling pressure of making ends meet so that they could carry the art form forward. In 2012, I began to talk with Guruji and the team at Chhandam about an endowment. While everyone could see the merit in establishing an endowment, it seemed like a fantasy. How could a small arts nonprofit raise millions of dollars? Three years later, the year of Guruji’s passing, I decided that it was imperative to establish the endowment. Guruji’s sudden passing forced me to face many realities. One of them was the harsh reality that time does not wait for anyone. I began to raise funds for the endowment in earnest. I am very grateful for those individuals who lent me their belief as I started work on the endowment–my mom and my dear friend Trina Chaudhuri. I am grateful for my guru sisters Rachna Nivas and Seibi Lee, who lent the idea their enthusiasm and belief. I am grateful to Dr. Ushakant Thakkar, who was the endowment’s first major donor. His support and encouragement propelled the work forward. I am grateful to the Leela Board of Directors as well as all of the community of donors that have come together to establish the first self-standing endowment for Indian classical dance and music.

You were the founder of the Chhandam LA branch, which eventually became the Leela Institute, and then led to the founding of the Leela Dance Collective with some of your guru-sisters. Can you talk about what led you to expand Chhandam to Los Angeles and how that led to the founding of Leela?

You were the founder of the Chhandam LA branch, which eventually became the Leela Institute, and then led to the founding of the Leela Dance Collective with some of your guru-sisters. Can you talk about what led you to expand Chhandam to Los Angeles and how that led to the founding of Leela?

My parents were an active part of the San Fernando Valley Gujarati Association in Los Angeles, and each year the association would host a culture show. As a high school student, I would choreograph folk dances for my peers and for young children in the community that would be showcased at the culture show. In 2005, after I had been studying kathak with Guruji for several years, the association invited me along with my guru sisters to come and perform at their annual show. Guruji was thrilled that I was going to be connecting my childhood community with the art form and trained and rehearsed five of us to travel from the Bay Area to Los Angeles to perform in the show. In 2006, I worked with Harkishan Vasa and Nitin Shah at the Jain Center of Southern California to present India Jazz Suites at the La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts. In 2007 a small informal classical music and dance group, the Kichchdi Club, founded by Vijay Bhatt presented my first full kathak solo at the home of Jitendra and Meena Mehta. And in 2008 the Chhandam Chitresh Das Dance Company received a grant from the James Irvine Foundation to expand its work to Los Angeles. I led that expansion and over the next several years built a base of students, audiences and patrons for kathak dance. It was my family and community support and Guruji’s encouragement that led me to build out Chhandam’s work in Los Angeles. Eventually it became clear that in order for the work to expand and reach more people, we needed a locally based 501(c)3 organization. On January 1st, 2015, four days before Guruji passed away, we began operating as The Leela Institute.

In hindsight, I can relay the story of how the founding of The Leela Institute and the Leela Dance Collective came to be–what events precipitated what and how the various events and activities strung together to eventually lead to Leela. However, to be honest, I was simply taking one step at a time. The only thing I knew for certain was that I wanted to make a contribution in the dance and bring the art form to as many people as possible. Each step was trial and error. I was guided and supported by the Divine, my family, Guruji, and an incredible community. I am eternally grateful to those first students and board members that took a chance on me. Two families, in particular, provided me with the steady support I needed to build Leela–Ruchi Mathur and Mark Pimentel and Swamy Venuturupalli and Rita SInghal. Core members of the San Fernando Valley Gujarati Association treated me like the community’s daughter and provided me with such incredible encouragement–Vijay and Swati Bhatt, Jitendra and Meena Mehta, Sumant and Chandrika Patel and Dinker and Aruna Shah. Harkishan Vasa and Nitin Shah at the Jain Center of Southern California took a chance on the dream I had. The founding of the Leela Dance Collective was organic and once again divinely guided. One year after Guruji’s passing, a few of us gathered at Lake Tahoe to reflect. We had no intention of founding the Collective. We talked about our experiences with the Company and reflected on how we could move forward. Our love of the dance and desire to work together fueled the idea of the Collective. Over time it became an experiment. We are still working out what it means to truly be a collective of artists and dancers. I am thrilled that the collective has produced strong artistic works such as SPEAK and Son of the Wind. What grounds the collective is a shared belief that we can accomplish more together than alone. With the pandemic posing a great threat to many dance companies and performing arts organizations, the collective is going to have to reflect, pivot, and reinvent itself for the new reality ahead. I am looking forward to engaging in this process with my guru sisters and fellow artists.

You received a prestigious Fulbright scholarship for researching the impact of kathak dance on marginalized young girls in India. What drew you to do this project, and how has that informed and shaped your approach to the dance?

You received a prestigious Fulbright scholarship for researching the impact of kathak dance on marginalized young girls in India. What drew you to do this project, and how has that informed and shaped your approach to the dance?

As a graduate student at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, I developed an avid interest in the link between women’s empowerment and health outcomes. Over the two years I was in school, I studied women’s empowerment in-depth. In the summer between my first and second year, I worked at a clinic in Kolkata, taking oral histories of sex workers in order to understand the complex and nuanced relationships they had with power. All the while, I was studying kathak with Guruji and beginning to understand and develop a relationship with my own personal power. My experiences in graduate school and in Guruji’s class began to integrate. At school, I began to see how a woman’s sense of agency and personal power is inextricably linked to health outcomes, and in Guruji’s class I experienced how the study of kathak can facilitate the development of one’s sense of power.

Throughout my career, I had worked with girls and women in immigrant and underserved communities in the United States. It seemed natural to connect my interest in women’s empowerment with my love for dance. I was lucky to have received the Fulbright scholarship. My project was made possible by my Guruji’s support and the support of my guru-sister Seema Mehta, who graciously hosted me in her home for the length of stay in India, invited me to be a part of her school and institution during my time in India and helped facilitate my Fulbright work. It was her passion for serving underprivileged communities in India that helped connect me with an amazing group of students. My Fulbright work continues to shape my teaching. It was that project that taught me how the dance can be a powerful container for young women’s emotional, spiritual, and intellectual development–and how studying kathak can cultivate a sense of agency and possibility in girls at a crucial age.

It was your brainchild to create the documentary, Upaj, on Pandit Chitresh Das and Jason Samuels Smith’s sensational collaboration India Jazz Suites. As Executive Producer of the film, can you describe how that came about and what the process was like?

It was your brainchild to create the documentary, Upaj, on Pandit Chitresh Das and Jason Samuels Smith’s sensational collaboration India Jazz Suites. As Executive Producer of the film, can you describe how that came about and what the process was like?

In 2007 I was working as the Development Director at the Center for Asian American media, an organization that works to elevate the voices and stories of Asian American communities on public television and beyond. That was the year the Chitresh Das Dance Company premiered India Jazz Progressions and Shabd. I had invited my colleagues to attend and was thrilled that almost all of them did. On Monday morning, shortly after I arrived into work, Stephen Gong, CAAM’s Executive Director, walked into my office and asked me why there wasn’t a documentary being made on Guruji and Jason’s collaboration. His question stunned me into silence. He insisted that there was a quintessential Asian American story behind the collaboration. With his guidance and the backing of the Center for Asian American media, I started into producing the film. I raised $10,000 to make an initial reel. I was very grateful to the many people that contributed to that initial pot of money – including Seibi Lee and Noelle Barton. I was very grateful to Shipra Shukla, who jumped into producing the reel, and Hoku Uchiyama, who directed the reel.

From there, we went on to raise more than $400,000 to produce and complete the film. Antara Bhardwaj came in as producer and led the project to completion, helping raise funds, recruit a production team, manage the final editing along the way. The folks at the Center for Asian American media were there to provide support along the way. Upaj premiered at the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival in 2013 and subsequently went on to be featured at many film festivals around the country and world. I remember feeling a deep sense of pride and satisfaction after the documentary was complete. I had seen audiences across the world erupt in spontaneous standing ovations after watching Guruji perform. But I will never forget the way audiences stood and applauded when Guruji and Jason entered the stage after a showing of the documentary. The applause was deep and slow, reverential and held for minutes after minutes. The applause was pregnant with respect, understanding, and reverence for what Guruji had lost, what he had fought for, and what he had given. I am eternally grateful for the team that made Upaj happen and feel deeply assured knowing that students, dancers, and audiences around the world and for generations to come will have access to Guruji’s story.

The month that Pandit Das passed away, you were supposed to have a gandabandhan ceremony with him, which sadly did not occur. What was Guru-shishya parampara to you? What did the ceremony symbolize for you?

The month that Pandit Das passed away, you were supposed to have a gandabandhan ceremony with him, which sadly did not occur. What was Guru-shishya parampara to you? What did the ceremony symbolize for you?

I was supposed to have my gandabandhan ceremony on January 25th, 2015 – the day of Saraswati Puja. Guruji passed away on January 4th. Even though there will always remain a sadness in me that we weren’t able to do the ceremony, I felt that guru-shishya relationship of two hearts already existed. As far as the guru-shishya parampara is concerned, it is the foundation of everything in Indian classical dance and music and it is absolutely necessary for the knowledge to transfer from one generation to the next. It is also necessary for both the full actualization of the guru and of the shishya. I believe that underlying the greatness of all the great artists is that relationship.

I am really blessed to have had a guru that was willing to be responsible for my education and my actualization, not only as an artist but as a human being. For me, becoming a shishya is a lifelong process; I will be becoming a shishya for the rest of my life as I continue to do the art and do the work. It’s not a static thing. You don’t become a guru or a shishya. It’s not a label. It is a way of being and doing that you have to step up and step into every day. Maintaining and sustaining the thread between guru and shishya with care and intention is most critical to the survival and thriving of the art.

What is the most valuable lesson you have learned from your experiences as a kathak artist and educator that the next generation of dancers could learn from? Do you have any words of advice?

What is the most valuable lesson you have learned from your experiences as a kathak artist and educator that the next generation of dancers could learn from? Do you have any words of advice?

When I walked into Guruji’s class, I was an entitled, Berkeley-bred young adult. I considered myself a proud feminist and believed that I had the right to a voice, a vote, a stake, respect, opportunity, and much more. I had a hard time with what seemed to be a diametrically opposed system of mores in Guruji’s classroom. There you were entitled to nothing. You were asked to show up, shut up and learn. You were asked to trust and obey Guruji. You were asked to surrender your power to him. And you were asked to set your ego aside every day so that learning could happen. If you did not, you could be assured that Guruji was going to beat your ego out of you. I resisted this way of being and doing for years. I fought Guruji as he was trying to teach me. Looking back now, I can see how I was a stupid teenager. I am not sure how, when, and why it happened but eventually, I let go and surrendered. That was when I started learning, and my dance and the path forward opened up for me. Everything became easier. The resistance inside of me had somehow melted. Time and time again, Guruji made demands of me that seemed unreasonable. He scolded me even when it seemed that I didn’t deserve it. He asked me to do things I didn’t understand. I learned in every instance to firstly try to understand and if I couldn’t, simply set aside my reservations, issues and do as I was told. I developed an unwavering trust in him. Guruji and the dance have demanded more of me than I thought I had to give. But once I put aside resistance and tantrum, I realized that I have untapped reservoirs in me. I rose to meet the demands.

As I have grown older and faced obstacles and challenges in life, the lessons I learned in his classroom have been invaluable. I understand now that we are owed nothing. We are blessed to have the things we have – families, loved ones, opportunities, homes, food, etc. I have learned to be humble and grateful in the face of all that I have. And I have learned to show up, work hard, be of service, contribute and surrender all of the rest to the divine. My advice to the younger generation is to let go of entitlement and cultivate an orientation of humility and service. To not take anything for granted. And to have the courage to be open-minded and open-hearted.

As your journey continues to evolve, can you describe your experience as a woman in the arts today, both as a kathak dancer and entrepreneur?

As your journey continues to evolve, can you describe your experience as a woman in the arts today, both as a kathak dancer and entrepreneur?

I get asked this question quite a bit, and I have spoken on a lot of panels that have to do with women in the arts and entrepreneurship. For the most part, I feel really grateful and proud to be a woman doing this work. I feel very lucky to be a woman at this time in an era when women have more opportunities than they have before. I feel blessed that I have inherited all the victories that my mom’s generation and her mom’s generation have won on behalf of women. I think about all of those unrecognized women who have struggled both on behalf of this art form and other art forms. I feel lucky I live in a time with technology that allows me to document my work. I feel responsible that given the opportunities I have, I have to make sure to take advantage of them. I feel I need to continue to make contributions on behalf of and for girls and women everywhere, and continue to ensure that the sacrifices and the struggles that the women before me had to go through were for something.

As a co-founder of the Leela Dance Collective, can you share your thoughts on the role that LDC plays and will continue to play in the global kathak community trained in Pandit Das’s pedagogy?

As a co-founder of the Leela Dance Collective, can you share your thoughts on the role that LDC plays and will continue to play in the global kathak community trained in Pandit Das’s pedagogy?

My hope for the Leela Dance Collective is that it serves as a sanctuary for artists who want to continue to learn, grow, exchange, experiment, and innovate. My hope is that it gives artists a home, a sense of community, and a safe space to do their work. I hope that as time goes on, the collective continues to widen its circle to welcome more diverse voices and genres as well as future generations.

Rukhmani Mehta

Rukhmani Mehta (previously Rina Mehta) brings a singular voice and vision to kathak dance. Rukhmani is a founding artist of the Leela Dance Collective, which brings together leading artists from around the world to advance a collective vision for kathak. Her original works include SPEAK, a kathak-tap collaboration; Chandanbala, the story of the revered Jain saint interpreted through the kathak tradition; and Son of the Wind, the story of the India’s mythological hero, Hanuman, brought to life through dance-drama. Prior to her work with the Leela Dance Collective, Rukhmani was a principal dancer with the Chitresh Das Dance Company, performing and touring with the company’s critically acclaimed productions including, Shabd, Pancha Jati, and Sita Haran across the United States and in India. She has also been a dedicated kathak educator for more than 15 years. She is the founder of Leela Academy, which education in kathak dance in the greater Los Angeles area. In addition, she is a regular visiting educator at kathak institutions around the world, and most recently developed an arts education performance with the prestigious Music Center on Tour program that introduces school children across Los Angeles county to the artistic and cultural heritage of India. Her work is grounded in the belief that kathak dance can be a powerful tool for empowerment and social change. She is the recipient of the prestigious Fulbright award and researched the effectiveness of kathak dance education as a social intervention in underprivileged communities in Mumbai, India. Rukhmani’s most ambitious initiative is the Leela Endowment, the first and only initiative of its kind, aimed at providing the financial infrastructure necessary for dancers to thrive and continue to advance India’s rich artistic heritage.

Leela Dance Collective

23650 Community Street

Los Angeles, CA 91304

P: 323.457.4522

E: info@leela.dance